Free Subscribers, this is last weekend’s Q+A, and I thought you might like to read it! I’m sharing this for free as a little end-of-year gift, but also as a way to say, “We’d love to have you join the paid membership for the summer!” This summer, we are engaging in a slow chat on three professional books (one in June, one in July, and one in August). The authors will be joining us. We’ll be sharing ideas and questions and low-key planning for the year ahead, and we would LOVE for you to be there. Here’s the lineup:

Paid members of the Moving Writers Community also get access to our complete archives, including more than 20 complete reading and writing units and FREE professional development webinars! Happy Summer!

Q: How do you think about a scope and sequence that crosses multiple years? How do you make sure skills are building and students aren’t having the same learning experiences over and over again? — Many Community members + chat and the administrator from my on-site PD last week.

A:

Reader, this is the book Allison and I have always wanted to write. Allison has affectionately named it Four Years a Writer, and it would be a four year scope-and-sequence for high school writing workshop. Heinemann says no one would buy it. :) And yet, this is what we think about all the time.

Creating a beautiful, functional, authentic workshop within our own classroom is a bold and worthy project. But if you get really lucky and you work with likeminded (or like-curricular-ed) colleagues and the writing workshop extends for multiple years, what do you do? How do you take those skills and deepen them, extend them? How do you transfer learning from year to year so that students aren’t just writing the same thing every year but are evolving?

I’m going to tackle writing curriculum today because it’s a bit more challenging than reading curriculum where texts naturally differentiate themselves a bit more. Let me first offer some principles of thinking and then give you some examples.

If we want multi-year scope + sequences that build year after year, here are some things we need to think about:

Teach in genres not just modes.

It’s nearly impossible to differentiate writing assignments when we aren’t specific enough about the exact authentic genre in which we want students to write.

(Remember: mode is the writing’s purpose; genre is the form that purpose can take.)

So, if every year you have students write an “argumentative essay”, that is going to feel — if not be — exactly the same every year.

However, if we think about authentic forms that argumentative writing can take, we can scaffold it up and make each year’s assignment distinct.

(P.S. You may notice that I never mention persuasive writing in this post, and that’s just because of my deep ambivalence about separating persuasive writing from argumentative writing. Aren’t you still making a claim? Aren’t you still providing support? Sure, persuasive writing might have a slightly different aim than argumentative, but I think teaching them as completely separate modes is strange. That’s just me.)

Build by increasing length.

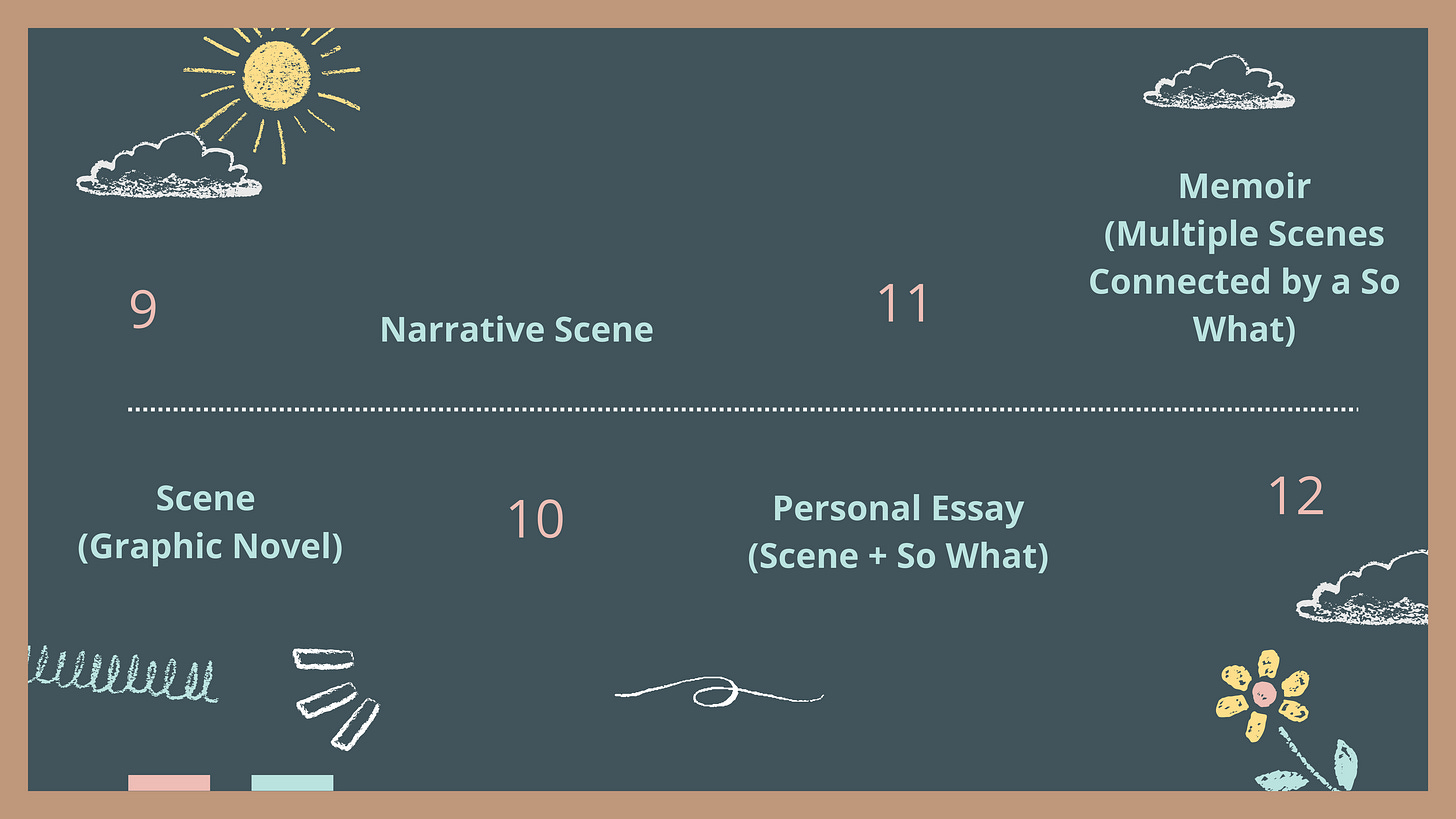

One way to think about building the writing year to year is to think about simply asking students to do MORE, to write longer each year. Look at this example for personal narrative:

While additional skills are being added at each grade level (adding a so what, connecting scenes, etc.), the biggest thing that is happening here is length. At first, in graphic novel form, students are doing very little writing. Then, maybe 1/2 page - 1 page for a narrative scene. Then 1-3 pages in a personal essay. Then maybe 5-10 pages for a mini memoir.

How can you find authentic genres of writing that increase the length of that type of writing each year so that students are writing more and more?

Build by mixing genres.

Okay, but here’s the thing about genre. It’s not pure. It’s almost never pure. A writer doesn’t compose something that is 100% informational — it might begin with a mini-narrative anecdote before moving into information. Or a piece of analysis might include a long informational section to give context.

For example, take a look at this fascinating op-ed that blends argument + information. Or this piece of informational science writing that begins with what I would easily call poetry. Or my new favorite literary analysis essay that is dotted with personal narrative.

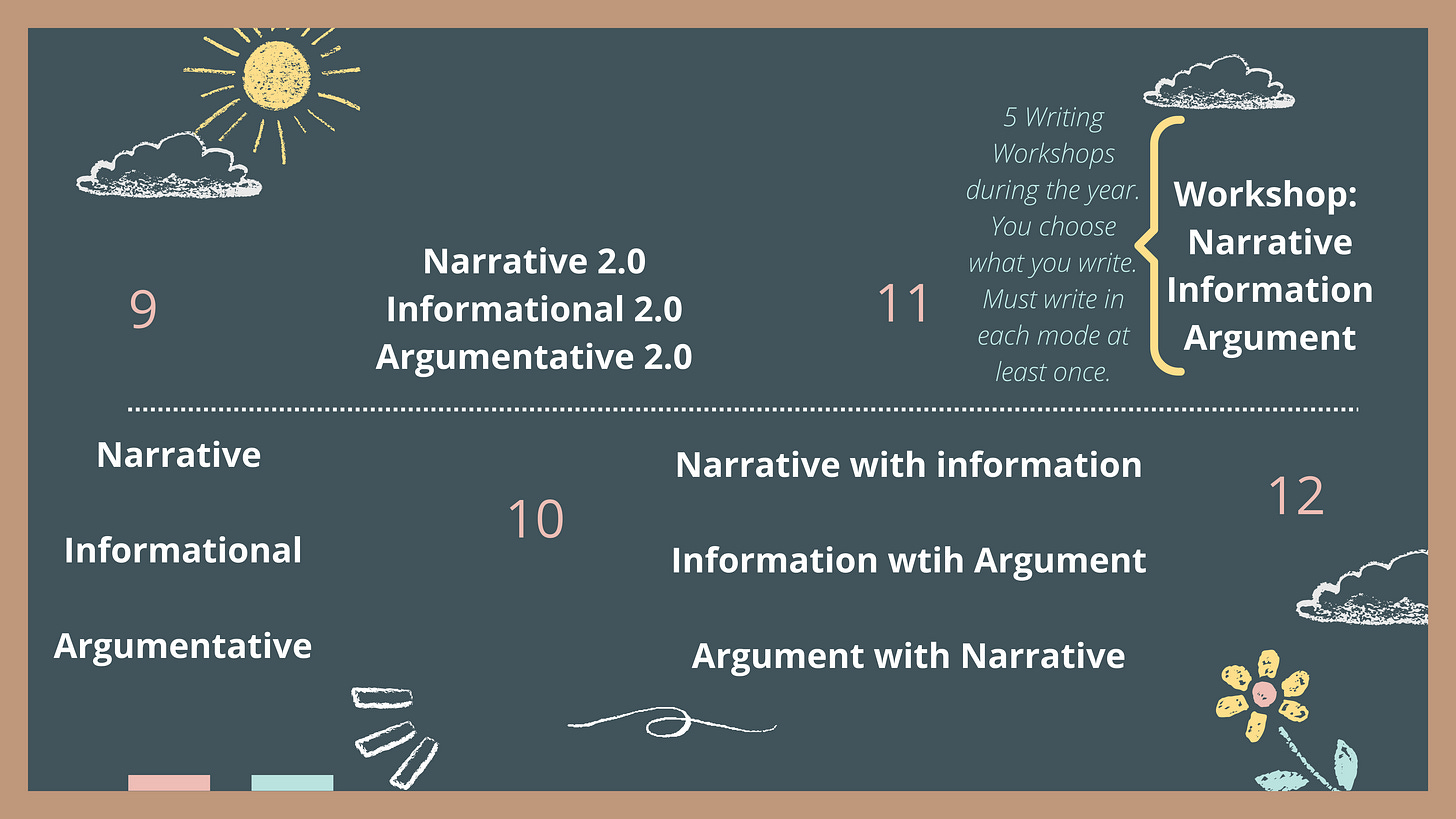

So, perhaps a way to build that scope and sequence is to teach the genres separately in earlier grades, but then start mixing and blending genres in later grades — not necessarily as “multigenre projects”, but as authentic pieces of writing that naturally dip in and out of multiple modes.

Build by offering more choice.

Just as important as our products are our processes in writing workshop. And offering an increasingly level of choice as students become more experienced and get older will also differentiate their writing experiences year to year. A few ways you might offer more choice:

Choice of mentor text: Invite students to find their OWN mentor text that they want to learn from and emulate. After students have had some experience with mentor texts, they can do this surprisingly well. (You might offer them some sources in which to look.)

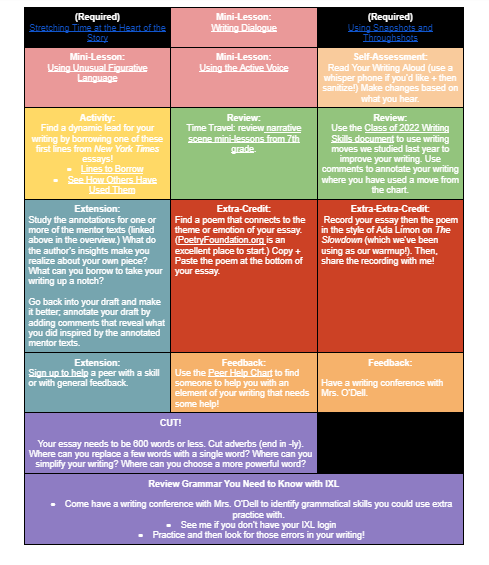

Choice of mini-lesson: As writers become more aware of their own personal writing process, of their strengths and their weaknesses, they can begin to select mini-lessons they need instead of being subjected to whole class mini-lessons that may or may not speak to the concerns of their writing. A choice board of digital mini-lessons can help balance requirements with options for writers and give students agency to choose for themselves.

Choice of mode: My dream is to run a secondary writing workshop the way Don Graves ran writing workshops with primary students. What do you want to write now? Okay, Let’s write it. Could you give your students choice of how they write and when they write it? What if, in the upper grades of your level, students are still required to do informational/expository writing and argumentative writing and narrative writing, but they got to choose which they did when. This would look so much more like an authentic writerly life as students choose what they want to work on, ensuring they have a sample of each by the end of the year.

Examples of Multi-Year Scope + Sequence for Writing

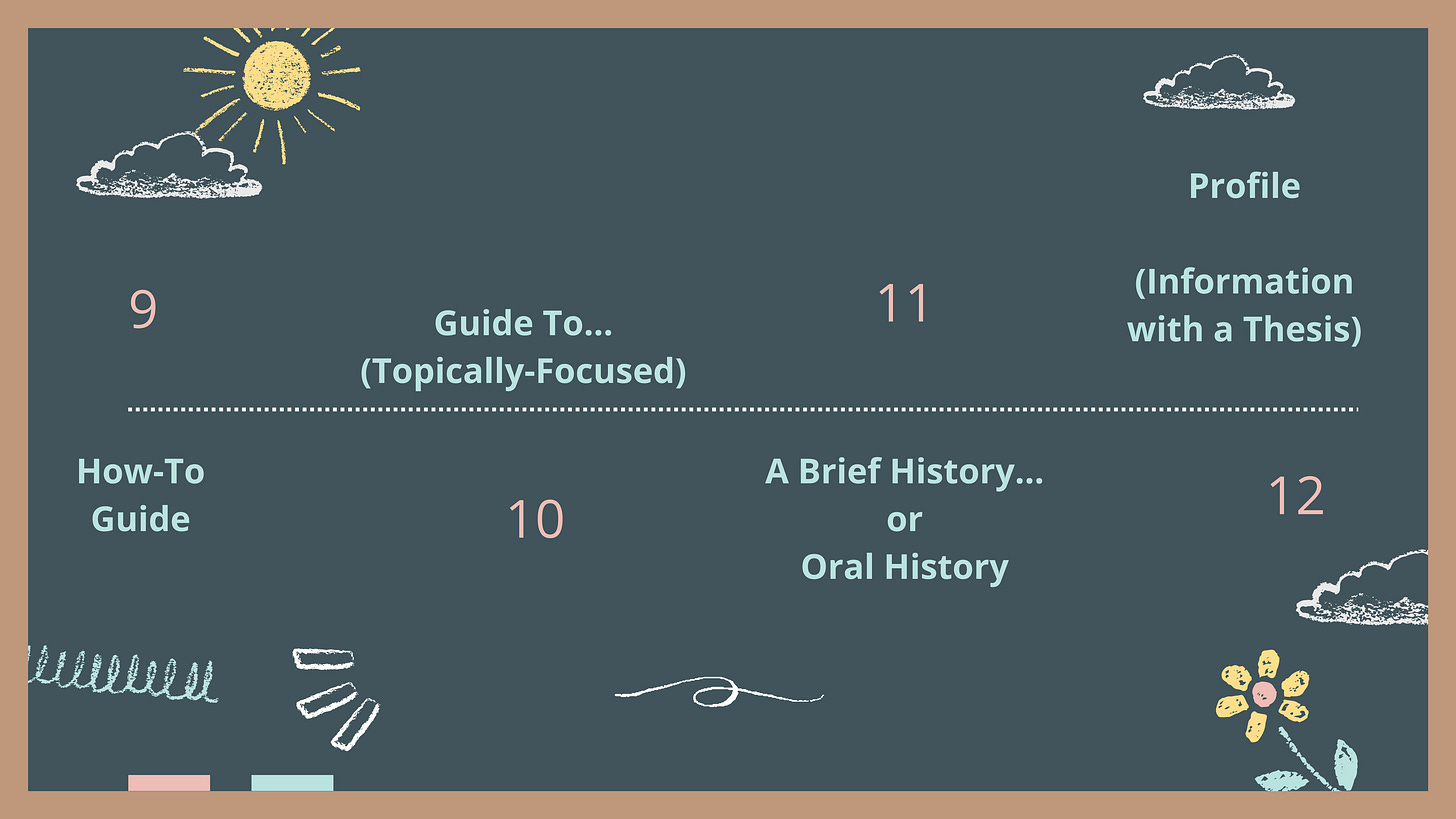

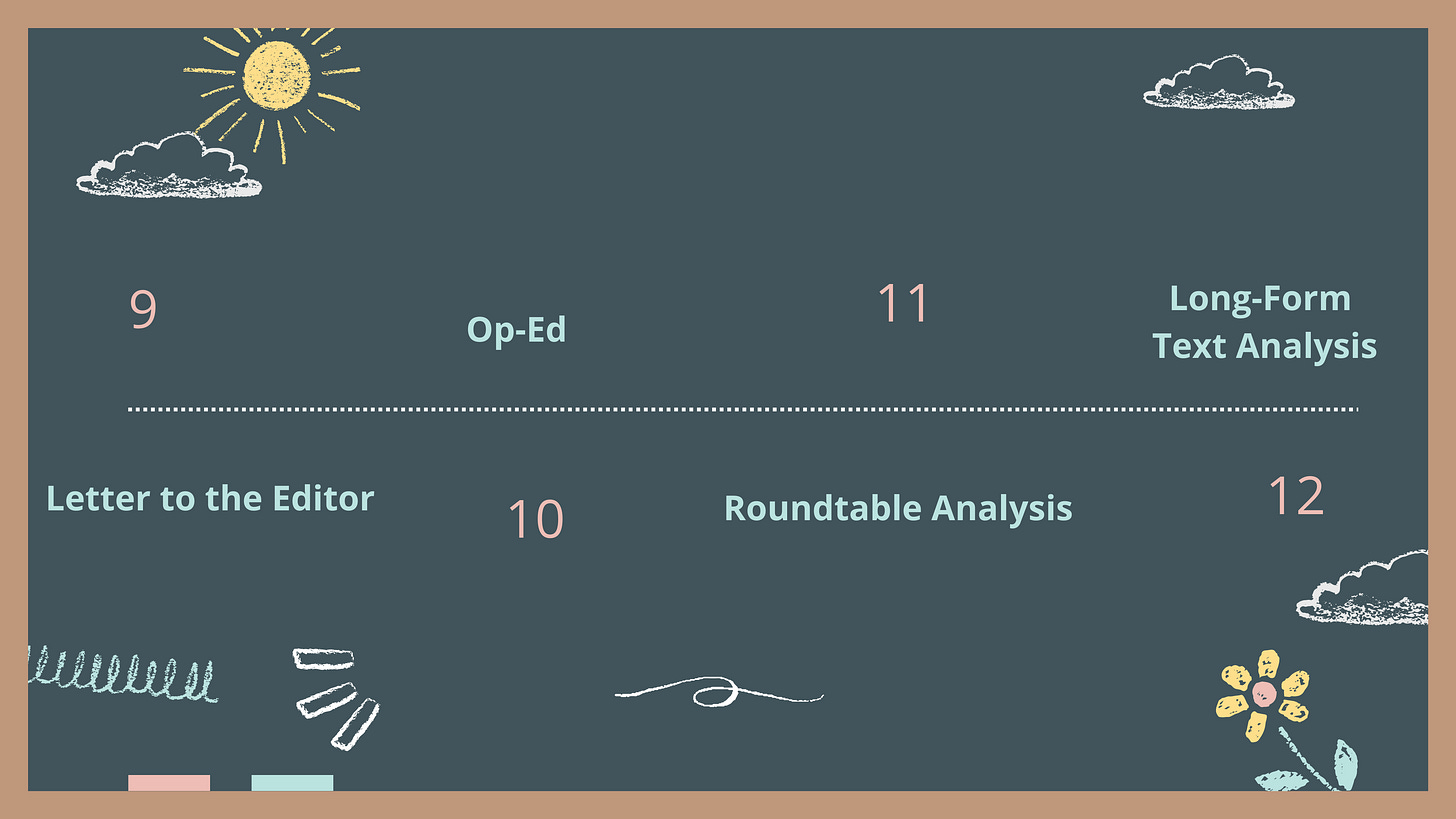

Above are examples of what narrative and argumentative/analytical writing might look like over four years. Here are a couple of other ideas:

Information Writing

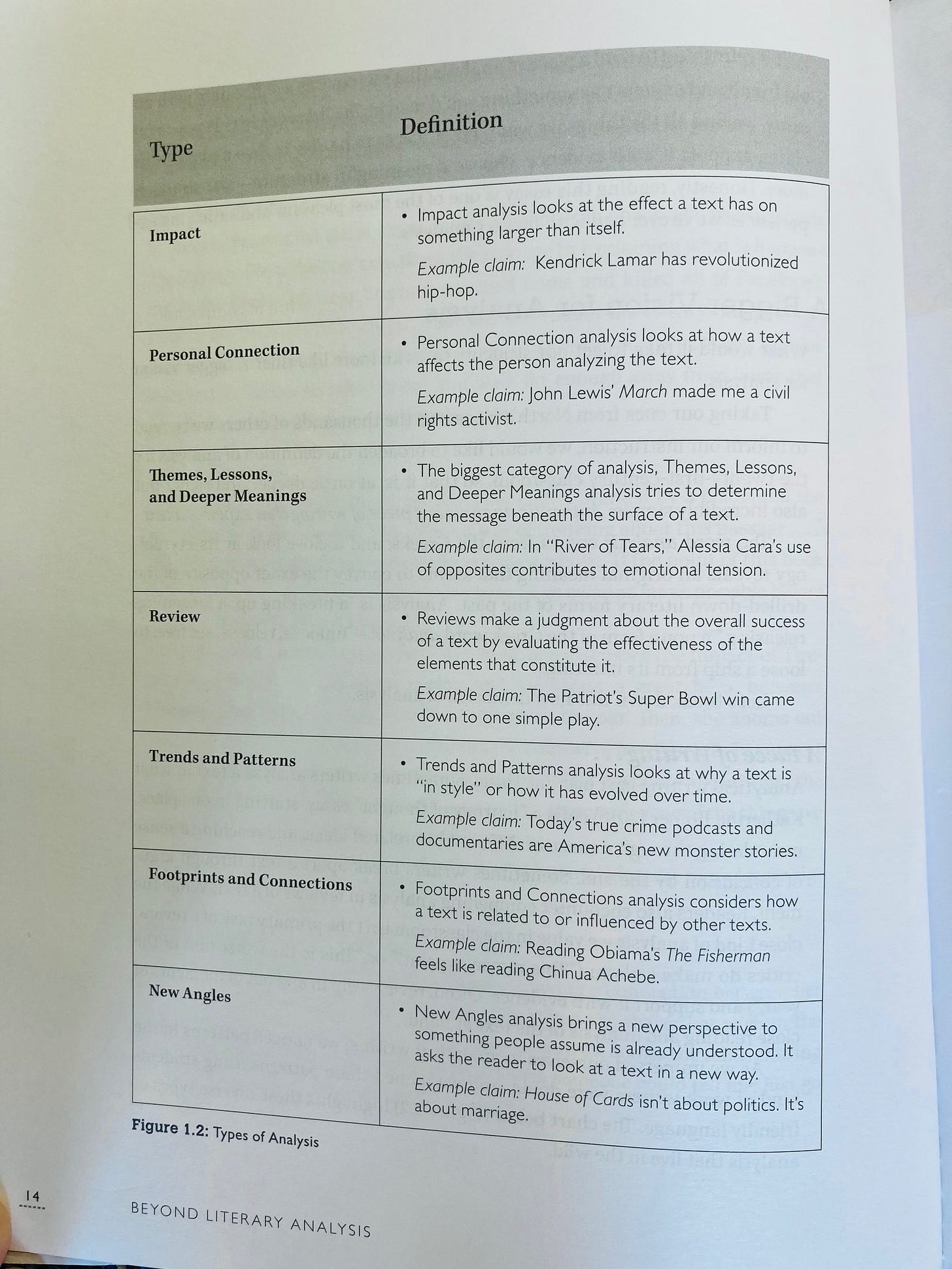

Text Analysis

This page of Beyond Literary Analysis is just one of my very favorite things ever, and it can help us so much in our thinking about how textual analysis skills can change and build:

Working Toward Independence + Blending of Modes

What if I am a lone wolf writing teacher on an island of my own?

Now, all of the above pre-supposes that you work in a department with likeminded teachers OR have administration that are super-cool and asking everyone to get in line with a scope and sequence of authentic writing products.

But what if you’re not. And they don’t. And it’s just you wishing you could make things better, but you are absolutely the only thing you can control.

I have been there.

To the degree it’s humanly possible, my advice is to let the rest go, try not to get caught up in fighting the man or changing the system (remind me of this Monday morning, please), and to do your best to make a responsive writing curriculum in your own four walls. Ask yourself:

Where are the gaps in my students’ writing experiences in other grades? For instance, if you know they only write literary analysis in the other grades, where can you create experiences they will be otherwise missing?

What can my students already do as writers + how can I build on that in authentic ways? Even if they are writing five paragraph literary essays in the preceding grades, your students do come to you with some strengths. Maybe they are adept at developing their ideas. Maybe they have a strong understanding of paragraph structure (albeit formulaic). Maybe they can write a three-part thesis like nobody’s business. This gives you a place from which to begin funneling those ideas into more authentic forms, breaking them out of five-paragraph structure, making their thesis statements more nuanced and sophisticated. What they can do already will inform what you do next.

What will my students need to do next as writers? What can I do this year that will support them on their journey? Maybe the next grade level assigns The Research Paper. As much as that annoys you, you know that your students will ultimately be more successful next year if you can provide them with meaningful opportunities for real research this year.

What experiences can you give your students that they won’t get anywhere else? When I taught high school, I taught a food memoir unit. We’d write food memoirs + then bring in the dishes we wrote about for a potluck. We didn’t need to write them; it didn’t meet any curricular objectives. But it was just good and life-affirming and fun and kids wrote AMAZING pieces about the ways in which a particular food intersected with their lives. What can you squeeze in just for the sake of its goodness because you know students won’t ever have that kind of writing experience again?

I’d love to hear what you think (and if the above is even helpful for those of you looking at big, sweeping curricular decisions)! Leave a comment to join the conversation about scope + sequence!